Protecting

the wild

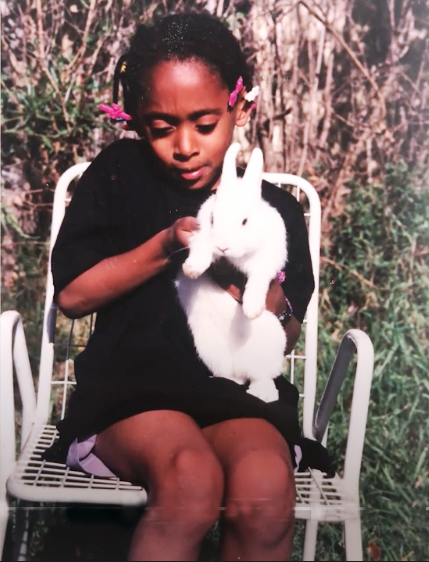

Rae Wynn-Grant conducted lemur research in Madagascar, and continues to monitor and provide care for bears and other wild animals. (Wildlife photos: Adobe stock. Rae Wynn-Grant with lemur: personal photo)

In addition to being the producer and host of NPR’s Going Wild podcast; co-host of Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom Protecting the Wild (yes, she achieved her childhood dream), and a National Geographic Society Explorer, Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant holds a full time research position in large carnivore ecology, environmental justice, science communications at the University of CA, Santa Barbara.Bradford Grant and Toni Wynn kept their free spirits well in check. Rae benefited greatly from their stability but her spirit demands to be more unbound, more true to nature. And therein lay the dilemma. Wynn-Grant’s memoir is a literal “both sides now” story. For the full scoop, the author is profiled here in three parts: Going Wild, Going Crazy, and Going Beyond the Book. Going wild

On a wilderness outing, Rae Wynn-Grant was trying to determine the mysterious cause of death of a bear. Performing autopsies had not been a part of her formal training but she resolutely hacked up the carcass, steeling herself against the stench and gore. After inspecting various organs, she reached into the bear’s stomach and pulled out the (surprising) contents. She shared the gruesome task equally with a co-worker and gained valuable on-the-job experience. The “failure is not an option” mindset aptly applies to her thinking. Afer believing that she lacked aptitude for mathematics (and learning doctoral level calculus), and after failing her oral exams (and succeeding in compensating for the failure), and climbing hills with weak newbie legs that almost gave out, and suffering imposter syndrome, and sleeping in the wilderness with a (self-described) weak bladder and a lion circling the tent, and being a vegetarian obliged to eat mountain lion stew, and, in her own words “struggling with self-esteem” and a deeper psychological crisis, after all of this, and more, she not only got over but excelled.Part of this woman’s brilliance is keepin’ it real. She has called that brilliance into question herself but it’s used here unreservedly because she shows that brilliance comes in various combinations. Qualities for success in STEM fields have been defined by white men in the West with a key criterion of “being good at math.” A key criterion of brilliance is problem solving, and a particularly ingenious form of problem solving is doing it any way you can, and not just the prescribed way.Raw moments of conflicts and caring

Conflicts and caring collide in Wynn-Grant’s work. One such moment was viewing bloody human parts that had been ripped apart by lions she knew by name. She had even named some of the lions herself and had come to love the pride. It was wrenching to grieve for the animals while grieving for the three children, two men and one woman mauled to death by the lions, and for the deceased people’s Masai community which she also loved. Her work encompasses both fieldwork and office-based research. The fieldwork involves a range of activities: walking for miles to locate species including endangered ones, tracking lion prides and other cohabiting animals and lone animals; capturing, anesthetizing and attaching monitoring collars to wild animals, and investigating how animals respond to environmental changes, natural events and human interventions. Back in her office, she analyzes the collected data, conducts spatial analysis using GPS data from collared animals to create statistical models that can predict their movement and behavior and determine if their habitats need to be marked for protection, and researches models to support her statistical methods.And as much as Wynn-Grant cares for animals, she’s even more concerned about human rights. Her community work focuses on balancing the needs of people living near wildlife with the needs of the animals themselves, a task she finds complex and often without easy solutions.When she was a doctoral student driving along an interstate to present a talk at her first professional conference, she heard about Michael Brown being shot by a police officer. At the conference, she was so disturbed about events unfolding in Ferguson that she “bombed. Bigtime,” she recalls. She wondered if these people, who would soon be her professional colleagues, cared more about the bullet hole in the bear in the slide behind her than the one that felled Brown. “I stumbled over my words and lost my train of thought and left the conference without attending other sessions,” she writes.Over the years Rae Wynn-Grant’s advocacy on behalf of disempowered people has become a defining aspect of her speech as a public science communicator. At the Bioneers’ “Revolution from The Heart of Nature” conference shortly after her memoir was published in April 2024, she pointed out the consequences for everybody when, in addition to their scientific work, black scientists have to attend to social justice concerns. “When a scientist comes from a community that is on fire, that scientist can’t focus on their science,” she said. “When their science is in service to the planet to create a healthy, thriving ecosystem, then we all lose." Going crazy

The second meaning of her book's double entendre title, Wild Life, seems to refer to the author’s own unbridled impulses that have led to much suffering.In the book, Wynn-Grant describes an emotional wilderness that paralleled her work in thrashing through real jungles with machetes. Her self-recriminations include wording like “selfish,” “reckless”, “ruined,” “self-hatred,” “shame,” “lost all dignity and self-respect,” and drowning in a “toxic ocean of chaos.” Her contrasting traits of true off the grid grit, roughing it in the wild vis-a-vis loving glamour (fashion, hair and make-up) and being very flirtatious converged in an extra-marital, love affair that began on a wilderness expedition, continued back home, and wound up devastating multiple. But as a caring and conscientious being, she felt guilt and depression about the consequences of her free spirited nature and sought psychotherapy. Being mindful of her young daughter also helped Wynn-Grant recover from depression.Wynn-Grant’s work-life balance is complicated. As an evolutionary biologist, she’s an expert on primate behavior including her own, and is, at heart, proud to be a passionate, sexually robust, adventurous woman, born free to roam across vast terrains, daring to live life on her own terms. Her calamities have chastened and modulated her, not changed her. The mating impulsive is primal; evolved animals need to know how to handle this primacy.One personal trait she views as problematic continues, but to a lesser degree. “I didn’t know anyone as obsessed with their career as I was,” she writes. But being obsessed gave her the courage and fierce determination to push through the challenges of training for, and working in, a difficult and dangerous profession.Unpacking conditions that led to her major crisis, she cites a factor that is particularly poignant: being “overlooked by so many smart, attractive, eligible Black men for years… .” She also wanted a man who saw “all that was nontraditional (emphasis added) in me as qualities to love.” That admission was wrenching for me for two reasons. Because like her parents, and aunt who recognized Rae's gamine with wide-eyed wonder, her dazzling toothpaste model smile and all of the other elements of her charming, inimitably Rae-esque beauty, I saw it too. We were not hoodwinked by corporate commodifications of women’s beauty and the popular media and prevailing materialist paradigm that upholds that commodification. We still knew what our ancestors knew: that real beauty is realized from the inside out, and not by emulating some narrow societal ideal.I also was touched because, a few years before Rae’s emotional crisis, her mother, Toni, and I collaborated on a screenplay that was motivated by young, black “non traditional” (i.e., unconventional) women who felt overlooked like Rae. But Rae has found a compatible life partner and has learned that her renegade spirit can be managed in balanced and yet still uncompromising ways.

Trading guilt and shame for a “how I got over” sense of triumph, Rae Wynn-Grant found the full self-realization that is her birthright (and ours, too).In having the courage to honestly and openly confront the most intimate and painful aspects of her life, she goes beyond being a professional high achiever to become an even more inspiring and heroic public figure. Going beyond the book

I rounded out this review by interviewing Rae Wynn-Grant as a family friend. My friendship with her family included Rae’s grandmother Loretta Wynn (1930-1923) from whom Rae inherited her distinctively graceful manner. In addition to telling me that Rae's grandmother Surlene Grant is also a unique paragon of grace, Loretta’s daughter, Toni, has told me many revealing things about Rae that were not in the book. For example, Toni noticed an early sign of Rae's protective interest in critters of all kinds when rain washed worms onto pavements. Little Rae delicately picked up the creatures squirming in discomfort and returned them to the earth. During the interview, I told Rae that a self-effacing remark she made in the book was far from being true. “When you said you were ‘overlooked’ by those guys, I thought ‘Dang Rae! That remark makes good copy but surely you exaggerate! I mean, like what about ____________?” I can’t identify the person who was going from being a major “name” in hip hop to becoming an international cross-over star when he met Rae who was then in grad school. This guy ain’t hardly overlook Rae in fact he looked her all over and hit on her in a nice way. Rae did acknowledge that her interaction with the icon was a “fun story.” And to infuse some juice into the blanks of the dialogue, she recalled her “big crush” on Allen Iverson (those cornrows and tats) and Michael Vick who “ended up going to jail but I interacted with him a couple times. He asked for my number.” Like many, younger, leading-edge ecologists, Rae has never been in the doom and gloom school of environmentalism. To put this school in perspective, I thought about the April 2024 Ebony magazine special issue on black environmentalists being entitled “Earth Warriors.” Warriors! But Rae and her close colleagues are saying, “Make love, not war” on the environment!

Of course, vigorous confrontation of environmental crises is necessary. The prep of this piece was accompanied by news about monkeys falling out of trees and venomous snakes forced to migrate closer to cities because of the heat; also the cascading effects of rising sea temps, toxic pollutants and microplastics on marine life, and other ominous aspects of the environmental polycrises (plural).We’re all literally feelin’ the heat. As I write this on June 7, 2024 record temps are being set in the state and region where Rae now lives. Yesterday, in Fresno, it was 107; Phoenix was 113 degrees, and summer’s not officially here. And in a June 5, 2024 report, the World Meteorological Organization said that over the next five years, there’s a nearly 90 percent chance Earth will set another record for its warmest year, surpassing the highs of 2023. So what’s love got to do with it? To explain, Rae began by looking back:I'm fortunate to be a child of the ‘90s and during that decade there are some really important conservation and environmental things that happened for the better. When I first understood what was going on with air and water pollution and pesticides, bald eagles were about to go extinct. DDT pesticides were getting into the ecosystem and causing the eggshells of bald eagles to be really thin so that the babies couldn't hatch. That was really unacceptable and the pesticide quickly got outlawed. Politicians, scientists, conservationists and farmers came together and changed that habit.When I was a kid there was also this big hole in the ozone layer because of aerosols and whatnot. And again everyone came together. Scientists said: this is what needs to change. Folks listened. Politicians enacted legislation. We have pretty much solved the hole in the ozone layer which was gonna be catastrophic for the earth.And the other thing that gives me hope is just being a scientist. We know exactly what our first, second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth and 10th steps should be to reverse this (potential) mass extinction.Rae knows many of the scientists who are developing these steps. They include her good friend, Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, who speaks about possibility as opposed to hoping that the environmental crises can be resolved.

The blurb of Johnson’s 2024 book, What if We Get It Right, expresses the love position, not war, on addressing the crises: “Our climate future is not yet written. What if we act as if we love the future?” In her “Is Water Alive” interview on Rae’s Going Wild podcast, Johnson cited the beneficial domino-effect practice of regenerative ocean farming: “And so thinking about these multi solutions where you’re sequestering all this carbon, you’re providing nutritious, sustainable food, you’re supporting coastal economies and communities, you’re providing all these jobs, and we’re talking about many, many millions of jobs in a sustainable ocean farming economy, you are rejuvenating life along the coasts. And that to me is just such a powerful future vision to hold onto. I mean, why would you not want that future?”Seeing possibility even where people only see devastation, Johnson pointed to Hurricane Sandy. Even though 85% of New York's wetlands were gone before the hurricane, the remaining 15% prevented hundreds of millions of dollars in damages and potentially saved many lives. So Johnson urges us to focus on the positive impact of partial conservation efforts, rather than viewing environmental action as an all-or-nothing proposition.“In her culture, everything, the animals, the plants, the land, the water, they’re all considered as relatives… .”

Rae was reminded of the previous Going Wild episode with a Tonga archeologist Desiree Renee Martinez who sees the personhood in all living things: “In her culture, everything, the animals, the plants, the land, the water, they’re all considered as relatives, and that’s a pretty radical idea” — a radical idea for the human supremacists that many of us have become, in the technopolis that many of us inhabit.

So what is this “What if we get it right” love? Ayana Elizabetth Johnson nails it and names it: “biophilia,” our innate sensibility. Biophilia! Love of nature!Our biophilic immediate forbearers had huge affection for animal relatives like Brer Rabbit. And before the days of our dear wise humorous trickster brotha, our people loved the venerable spider, Ananse, in West Africa. We thanked the trees and animals before felling them to make shelter, utensils, food and clothing. The spirits of winds like Oya and waters like Yemana were our sisters. Yes, Drs. Rae and Ayana, the water is alive in ways both mythopoetic and literal. In black and brown traditional cultures within living cultural memory, people wore feathers in their hair as a symbol of the empowering relations within the realm that some early European anthropologists and philosophers called “animistic” and “pantheistic.”Our ancestors within living cultural memory knew the biosphere is alive and were biophiles before 1970 when chemist James Lovelock and biologist Lynn Margulis formally introduced the Gaia concept of Earth as a self-regulating, living being. Doing hard things

Asked whether she has any advice for doing hard things, Rae’s thoughts first turned to writing the memoir: “It was very clunky and very stressful pretty much the entire time. But a lot of the time I was (also) trying to wrap up other tasks. And I had a very strict deadline -- like my contract would have been just shredded to pieces. So, it was really stressful and yet somehow kind of emotional and enjoyable” after the narrative took shape and began to flow. Rae was learning what both masters of writing and woodworking know: you have to work through the rough parts to achieve smooth results.On meeting the challenges of working in the field, she said: “I have taken day-long 14 hour hikes into the Congo Basin. I have tracked across the Great Plains for 10 hours. I have done a lot of these endurance-based things and I really don’t think I’ve done any of them gracefully.” Then she recalled other challenges: There was a point when my marriage was ending, and the ball was in my court about whether it would end or not. At that exact same time (I had to decide) whether I stayed in my postdoc at the American Museum of Natural History. It was an impressive, high level, fully funded postdoc that I could have stayed in for another year, if not longer. There have been several times I have felt very much called to just bet on myself. I don't know if I'll get to what I want but I know that it's up to me to try and even trying will put me somewhere better than where I am.In the memoir, Rae recalls that her post doc position at the American Museum of Natural History included speaking on environmental topics at various places. When museum officials expressed their discomfort about her referring to racial matters during these talks, Rae was not comfortable being the black woman equivalent of a “company man,” a worker who automatically acquiesces to questionable company policy. So Rae bet on herself and resigned.During the post doc at the museum, Rae had met Neil DeGrasse Tyson who said he was pleased to see another black person working there. (Tyson directs the Hayden Planetarium at the Rose Center for Earth and Space which is part of the American Museum of Natural History.) When I read about Rae’s encounter with Tyson, I thought about her father Bradford Grant’s telephone interview with Tyson shortly after the Rose Center opened in 2000. Brad was interested in the architectural design of the center’s new building and, after inquiring about the design, asked Tyson about the Dogon astronomers of Mali. Although he was aware of skeptics who discounted Dogon astronomy, Brad was intrigued by it. Brad told me that Tyson scoffed at the Dogon astronomers rather than expressing any interest in their deeply cosmological culture. So it was reassuring to read in Rae’s memoir that when she and Neil DeGrasse Tyson conversed, he expressed solidarity with her as a fellow West African descendant. Some, maybe even much, of Tyson’s genius stems from the African branches of his genealogy.Rae's daughters, Zuri and Zooey, only know a perambulating mommy so they don't cling when she takes off. They get great support from Rae’s partner, Dave, an independent filmmaker; members of Rae’s immediate family, and the strong co-parenting relation between Rae and her former spouse. Zuri wants to be an “insect scientist” (entomologist) and also says she wants to be a singer and performer. Like mama, like daughter: after classical vocal training and performances in Norfolk, Rae released tension from doctoral study by rapping on a Brooklyn stage. The “career obsessed” (as she describes herself) Rae says she’s beginning to decompress: “I've learned a lot about how stress affects my body and my health and my mind. Slowing down, doing less, feeling more, is really important to me as I turn 40 next year (2025).” Rae wants to be at home more when her girls enter adolescence and would like a hobby; she hasn’t had one as an adult:Sometimes I think yoga is my hobby. Yoga is the only consistent thing I've done since I started in grad school and it makes my body feel good. But I really would prefer a hobby that isn't necessarily productive. So I'm considering tennis or pickleball or cooking more from cookbooks. “Cooking” is getting close to my recommendation that Rae’s hobby be gardening. Her mother Toni cultivated a beautiful, bountiful raised bed garden in the backyard of her Hampton VA home before selling the house and moving to NYC to support Rae and baby Zuri.Gardening has everything Rae would want in a hobby—the untamed feeling of soil beneath her fingertips and bare feet, rising in the morning and going straight to the garden in her nighties to stretch to birdsong and pick dewy parsley, mint and cherry tomatoes for her tabbouleh and plucking a melon in the still soft sunlight. It’s all over body motions that compliment her yoga practice and strengthen hands and fingers in particular ways. It’s the pungent smell of volatile oil from clipped basil leaves and fragrance from sweet alyssum, Mexican orange blossom and wisteria. It’s the confidence of knowing that the food she’s eating is completely uncontaminated. It’s life sciences observed closeup: how worms help fertilize and insects help pollinate the garden, how root systems radiate, what plants grow synergistically with others, and why chrysanthemums repel aphids. It’s food with the strongest flavors and nutrients (the vitality decreases as soon as plants are pulled from the soil). Not to mention the magic! Oh, go on and mention it. Toni, who lived alone when she had the raised bed garden, was astonished to find the little wooden bird that she kept in the bathroom among the plants in one of the raised beds. Somehow it got there on its own!

During our interview, Rae concluded her comments about optimism in the midst of environmental crises with this remark: "We're already taking steps towards a pretty bad possibility for our future so how about the good ones? I feel very aware of all of the choices that are on the table and I look forward to when the people or communities with power choose the plans that can put us in really good shape." Rae Wynn Grant for POTUS?

When I heard Rae speak about being "aware of all of the (evironmental protection) choices that are on the table," I thought about the influence that she would be wielding if she had accepted the position of director of the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Rae declined that substantial, career-advancing job offer because she was just settling into a university research affiliation in Santa Barbara, CA, and had just given birth to her second child.Directing US Fish and Wildlife can lead to the presidential cabinet position of Secretary of the US Department of Interior during the Biden administration. Rae Wynn Grant is continuing to advance on multiple professional fronts and could embark on an upward trajectory at Interior by the time she’s in her early 50s and her younger daughter is completing high school. By then she will have fortified her credentials and connections and after serving at the helm of Interior, Rae would be in a good position to take the next step. Could that next step be running to be the president of the United States? Former U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland is running for governor of New Mexico. Interior to POTUS is not such a long shot. As an environmental scientist, Rae Wynn Grant not only sees the "big picture" but all levels and scales of the picture. She has a strong work ethic and routinely confronts daunting challenges. Her extensive skill set ranges from statistical analysis to conflict resolution. She travels all over world and this nation and feels right at home at the Montana State Fair. She has a genuinely deep humanitarian consciousness and is a captivating public speaker. So POTUS? Why not?In the meantime, another vision emerged: Motions may be beginning to stir for an epic movie based on Rae Wynn-Grant’s Wild Life memoir. Her incandescence has always been star quality and now she’s told a deeply moving, truly heartfelt, one-of-kind story that’s begging to be put on the big screen. Anyone who’s read the memoir can envision it as movie filled with spectacular outdoor adventure and sizzling romance. A big blockbuster “shot on four continents with a cast of thousands” (including the mosquitoes) and gorgeous, panoramic nature photography. J.H.(Get photo sources)

Lion attacks zebra in Naboisho, Narok, Kenya

Photo: Meg von Haartman on Unsplash

“Saving nature means saving ourselves…. When a scientist comes from a community that is on fire, that scientist can’t focus on their science,” said Rae Wynn-Grant at the “Bioneers Revolution from the heart of Nature” conference.

ecollective

Thrashing through an emotional wilderness when the mental monsters became real.

Four generations: Loretta Wynn and Surlene Grant, Rae Wynn Grant's grandmothers, and Rae with Zuri in utero before 2015 Columbia University commencement where she received her doctorate. Toni Wynn was on the scene taking the shot. (Photo: Wynn-Grant collection)

Rae Wynn-Grant searches for hibernating bears. (insert photo source)

Rae has always loved animals and grew up to be the woman of her dreams.Wynn Grant family photo.

Rae Wynn-Grant and daughter, Zuri, at sunset on Fort Monroe VA beach, August 2015. Photo: Wynn-Grant collection

Rae Wynn-Grant with her parents, Bradford Grant and Toni Wynn, and David Seligman, her partner and father of her second daughter.

Photo: Wynn-Grant collection

Archeologist Desiree Renee Martinez advocate of “biophilia.“ (personal photo)

The American Museum of Natural History in New York City. (Photo: Ingfbruno, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

In addition to co-hosting Wild Kingdom, Rae Wynn Grant is an affiliated researcher with the Breen Schook of Environmental Science and Management, University of California Santa Barbara

Will Rae chose gardening as a hobby? The photo shows a partial view of her mother Toni Wynn’s garden in the backyard of her Hampton VA home, circa, 2015. Toni sold the Hampton property when she moved to be closer to her own mother in New Jersey and provide child care support for Rae who was living in NYC. Toni Wynn's next move will bring her closer to the land.

Tears and fears and feeling proud

Rae Wynn-Grant on the trail.

(Personal photo)

Rae Wynn-Grant’s story reaches into the wilderness where her most frightening experiences as a wildlife ecologist occurred.And at the story's nadir, she speaks from a wounded heart and shattered emotions to inspire us to have the courage to heal. This honesty took just as much courage as some of her forays into the wild. The title of her memoir, Wild Life, is a double entendre meaning venturing into her own emotional wilderness as well as the wild places of the world.Lyrics from Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now” conveys the profound depth of Rae Wynn-Grant story in Wild Life: Finding My Purpose in an Untamed World (Zando/Get Lifted books, 2024).One side of Rae Wynn-Grant’s “both sides now” story recalls plunging into self-condemnation that, at rock bottom, threatened her sanity. The other side shows how extraordinary achievement can result when a young person aspires to full self-realization, doubts their own abilities and develops greater self esteem in the process.Born in 1985 in San Francisco and growing up in California, Ohio and Virginia, Rae Wynn-Grant lived in a household characterized by responsibility and respectability but was unconventional in some ways. Rae inherited free spirit tendencies from both her architect dad, Brad, and writer-museum consultant mom, Toni.The Wynn-Grant family TV was kept in a closet and removed only for educational programming and NBA games. From watching nature shows, Rae’s first and continuing ambition was to become the future host of “Wild Kingdom,” originally hosted by the renowned Marlon Perkins. Her ambition gradually expanded to include actual wildlife conservation science. And she’s now on track to achieve the kind of science educator recognition that Neil DeGrasse Tyson has as a popular science communicator. Marine scientist Ayana Elizabeth Johnson during community consultations for ocean zoning in Barbuda with the Blue Halo initiative. Photo: Will McClintock