Illustrations by Archana Hande for Ajman Sobhan’s book, Journey to Silence

Searching for transcendence in the world and through it

Ajmal Sobhan survived heavy smoking when he was a surgical resident and is now healthy and physically active. As his appreciation of the human body's resilience has grown, so has his recognition of how the natural world is an extension of himself, and he of it.

This connection is becoming increasingly clear during his long walks at an animal shelter. He is understanding how the apparent separation between himself and the world occurs within a single unified consciousness and this understanding complements his search for what he calls “transcendence.”

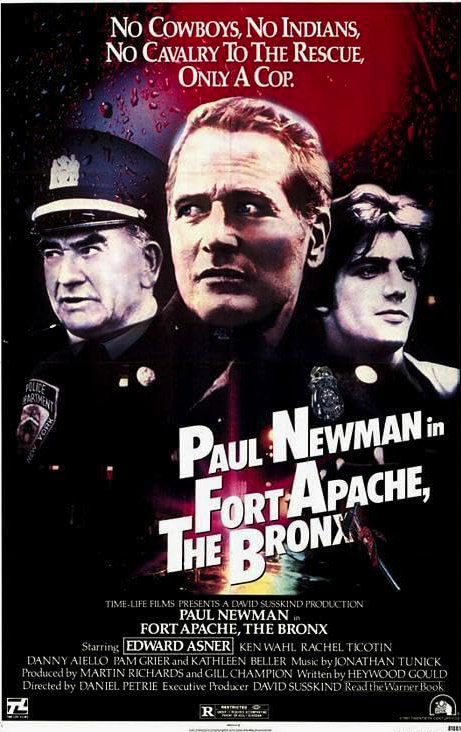

For many years I ran solo and in marathons, trekked across various terrains and progressed to mountains. I still take long treks but, on a cumulative basis, cover more ground walking three or four times a week at the 23 acre Animal Aid Shelter in Newport News VA. These outward ventures help propel an ongoing inner venture: seeking release from identifying with the personal self. The varied terrain at the shelter is bordered by a river. Walking through fields, thickets and woods with my dog is a release from my own mental cages.The dogs love to stretch out on the lush turf near the shelter! It’s a luxurious relief from their cage floors.My self-centered identity is emerging into a larger presence that I believe we all essentially are. The process will not be complete until I am subsumed by it. The dogs help in the process. It’s amazing how innocent and giving they are. Such spontaneous gestures! Licking your face or going belly up in surrender. They're the holy grail of meditation practice: pure joy absent any thoughts. The only time we see a scared dog or a dog that tries to hide or bite is when their previous owners were less than kind. It is so sad to see that, especially a malnourished dog. The lack of an intellect, not intelligence, makes the dog an intelligent being who has a very generous spirit. The human intellect is a double-edged sword. It is critical to make wise decisions and provide pointers for escaping the ego’s grip but it also intensely reinforces its own intent to bind us to superficial selves. Caring for animals loosens the grip. Mutual aid society: I walk the dog and the dog walks me.My great dane friend, named Mousse, greets me at the shelter.This January morning was partly cloudy and 24 degrees as we walked and trotted. Very cold for Hampton Roads. Tall trees with bare branches, pathways piled with leaves. The dog, myself, the solitude. The moment was more spiritual than prayer. That still moment passed as stillness always seems to do, but set the tone for the day. In the ordinariness of everyday life and in difficult moments, I try to remember that silence is the voice of God. It’s not always easy to be so focused. The goal is to surrender to this silence – stillness that is a very strong presence, not absence – to totally surrender to this presence that the ego finds so uninteresting and boring. I’ve come a long way. In 1978, I turned 30, was fresh out of surgical training at a Bronx hospital, and was a wreck not unlike the ravaged South Bronx policed by the cops who I met at Fordham Hospital nicknamed "Fort Apache." I was a pack-and-a-half-a-day smoker who woke up every morning, coughing and expelling copious amounts of phlegm. The stress of being a trauma surgeon working often 80 hours a week was the ostensible reason for my nicotine habit. There were so many gunshot wounds, stabbings and other inflicted injuries, it was like working on a war front. From 9 pm to 7 am, the action in the emergency room was non stop. I had a full beard and long hair. The cardiac chief of a Phoenix hospital, where I applied for a fellowship, let me know indirectly that the beard and smoking had to go if I was to work there. I tried to clean up my act but it was not easy. My chief at the Bronx hospital saw that I looked haggard and was coughing. “Ajmal, start running a few miles, you won’t feel like smoking anymore,” he correctly predicted. Six months later, I ran my first 10k in 48 minutes. I was happy with the outcome. Over the next decade and a half, I ran numerous 10Ks, half marathons, and three full marathons. My runs and treks back home in Bangladesh were far more adventurous. There I hooked up with Brother Donald, my high school teacher who loved biking around the country and trekking mountains. A lay priest from Kansas who had been sent to Bangladesh by the Brothers of the Holy Cross order in his 20s, and then was in his late 70s, Brother Donald found an eager outdoor companion in me.Brother Donald was just as excited about the partnership and taught me as fast as he could about the fine points of trekking and summiting. “This might sound like blasphemy for a priest but I would rather be in the mountains than cloistered in a monastery," Brother Donald told me when he took me to Nepal and introduced me to the Himalayan mountain chain. After my return to the States, Brother wrote me long notes about how I could go up to Everest Base Camp and what would be the best route to take. He had emphysema from his one vice, smoking and knew his life was ending. I feel he got vicarious pleasure from knowing I would pursue the path (both spiritual and physical) up the mountain for him as well as myself. During another trip to Nepal, I was the second oldest guy in the group. In eight days, we trekked up to14000 feet. It was not easy, but we managed. The company was good, the porters indispensable, the scenery like dropping into movie with vivid panoramic cinematography. And the silence broken only by the tinkling bells of passing yaks.The winding trail of Sobhan’s trek. Photo: courtesy of Ajmal Sobhan’s trekking partner, Sujoy DasPhoto: courtesy, Sujoy Das

Reaching Annapurna Base Camp, heart pounding, mind clear, gazing at the vast sky above was a deepening connection with something larger than myself, that is also my self: the one, all-encompassing self of essential consciousness that we all share.

(This essay is the first in a series)

After retiring from vascular surgery practice in the United States, Ajmal Sobhan organized and led medical missions to his home country, Bangladesh. The Covid epidemic disrupted the full mission but it has resumed on a smaller scale.

In addition to his medical missions and volunteering at the animal shelter, Ajmal Sobhan also delivers Meals on Wheels.

On January 30, 2025, after making deliveries, Sobhan emailed the message below to friends and associates, including the Ecollective. We are posting it here as part of our response to the urgent challenges to democracy posed by the Trump administration.

Earl, 69 years old, has been receiving meals for the last four years that I know.

Earl had cancer of the colon, had surgery and chemo and is on remission.

He used to work at Smithfield as a butcher.

He lost his job after his cancer came and he ended with opioid addiction.

He has moved three times with Section 8 housing,

Always looking for a better place but not getting it.

Meals on Wheels is destined for the chopping block.

Both state and local funding is drying up.

Routes have been reduced.

There are 200 people on the wait list.

As the (MAGA) country looks to be more prosperous with the new administration,

those in the margins are becoming more vulnerable.

Closing the doors on those who have difficulty surviving is not moral or ethical.

It serves us all to contribute to those who need it most.

Ajmal

Photo: Ajmal Sobhan

Ajmal Sobhan is on the right end of second row (in black jacket). Everest base camp expedition mates. Photo courtesy of Sujoy Das, a member of the group.(Need to identify Das if he’s shown in the group)