Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying—Typhoon Coming On) and detail from painting. J.G.W. Turner, oil on canvas,1840. Collection Museum of Fine arts, Boston.

“The water brings, the water takes” — Gullah Geechee saying

The environment is one of three elements investigated by a new study of the Gullah Geechee coast

The water brought European settlers and enslaved Africans to the Americas. The ocean water, now warmed by a changing climate, stirs up more powerful hurricanes like Helene, which lashed out at Asheville, NC, and other parts of southern Appalachia in an unprecedented hit for a mountainous area. The October 2024 hurricane caused 104 verified fatalities, seven people are still missing, and mudslides and wreckage of the built environment stretched across six states.

Water has been a significant “give and take” force in the natural and cultural histories of the southeastern coastal United States. In Romancing the Gullah in the Age of Porgy and Bess, the ocean, rivers, mud flats, marshes and other environmental elements are a critical focus that author Kendra Hamilton integrates with other areas of investigation.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, American studies — the Western world’s first fully interdisciplinary university degree program — was birthed by books such as Marx’s Machine in the Garden, Kouwenhoven's Made in America: The Arts in American Civilization, and Smith’s Virgin Land. “To read ‘Virgin Land’ is to experience a deep intellectual excitement,” wrote one reviewer.

The excitement stirred up by these and other foundational works of American studies was based on their fresh approaches to understanding familiar aspects of American culture. Their sophisticated analytical methods drew on a wide range of sources, including popular culture, giving them more relevance than single discipline approaches in addressing important questions about national identity and the nation’s place in the world.

And now Kendra Hamilton’s Romancing the Gullah in the Age of Porgy and Bess will have a similarly thought-provoking and catalytic impact on Southern studies and African American studies, as well as American and global south studies in general.

The "romancing" refers to how writers, artists and singers of the 1920s-1930s Charleston Renaissance interpreted the history of the rice plantation and Gullah Geechee culture in favorable and demeaning ways ranging from great insight, brilliant artistry and paternal fondness to crude caricatures and exploitative, mercenary expression. Hamilton occasionally uses post-structuralist analyses with a deft touch to reveal the underpinnings of the appropriation paradox.

Along with the extensive documentation of rice cultivation and Gullah Geechee folk ways, the Charleston Renaissance luminaries were buying and selling a lucrative, nostalgic “fantasy,” Hamilton says.

Kendra Hamilton loves intricate investigation but abhors dry exposition. Her talents as a writer of creative nonfiction and poetry add originality to her scholarly voice, and her background as a full-time newspaper reporter gives her the chops to write with maximal lucidity.

Hamilton’s environmental anthropology encompasses not only biological adaptations but also cultural practices, social structures and economic systems shaped by the interactions between humans and the environment. Hamilton integrates this approach with close scrutiny of Gullah Geechee genetic lineages and linguistics, making the book a scholarly tour de force that offers a wealth of seminal insights into what she calls "a shadow canon.”

Gulluh Geechee Corridor landscapes and waterscapes converge in Hamilton’s survey of a region that was once filled with rice fields.

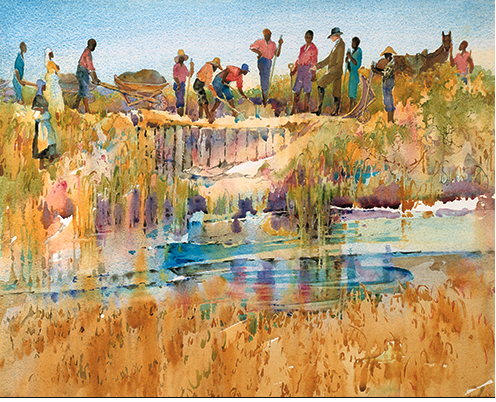

Alice Ravenel Huger Smith (1876 – 1958) Mending a Break in a Rice-Field Bank, from the series, A Carolina Rice Plantation of the (Eighteen) Fifties, ca. 1935, watercolor on paperboard (pre-conservation), Gibbes Museum of Art. Photo: courtesy of The Gibbes Museum of Art/Carolina Art Association

Hamilton says that “…the massive hydrological systems constructed to support the cultivation of the crop are not just legible but unmistakable. The imprint of this hand-and-mule-built system of dams, dikes and floodgates (or ‘trunks”) — pathways that partitioned the swamps into regular rectangular fields that then could be flooded and drained with the movement of the moon and tides — is quite literally carved upon the earth.”

Beyond the rice fields, water ways, not roads, were integral to the development of the South Carolina coastal plain. The landscape is marked by an extensive riverine and creek network including the converging Ashepoo, Comabahee and Edisto rivers, and the Broad River and Saluda River meeting to form the Congaree River. Beyond are the the rich brackish estuaries where the fresh river and salt ocean waters meet.

Map showing the eight major surface-water basins in South Carolina.

Source: the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources

Fourth of July celebration, 1939, St. Helena Island, South Carolina. The islands off the coast of South Carolina and Georgia, known as the Sea Islands, are a chain of over a hundred tidal and barrier islands stretching along the Atlantic Ocean coast. The building shown in this early color photograph today houses the Gullah Grub restaurant.

Photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor

Zora Neale Hurston, renegade queen of southernmost Gullah Gechee culture

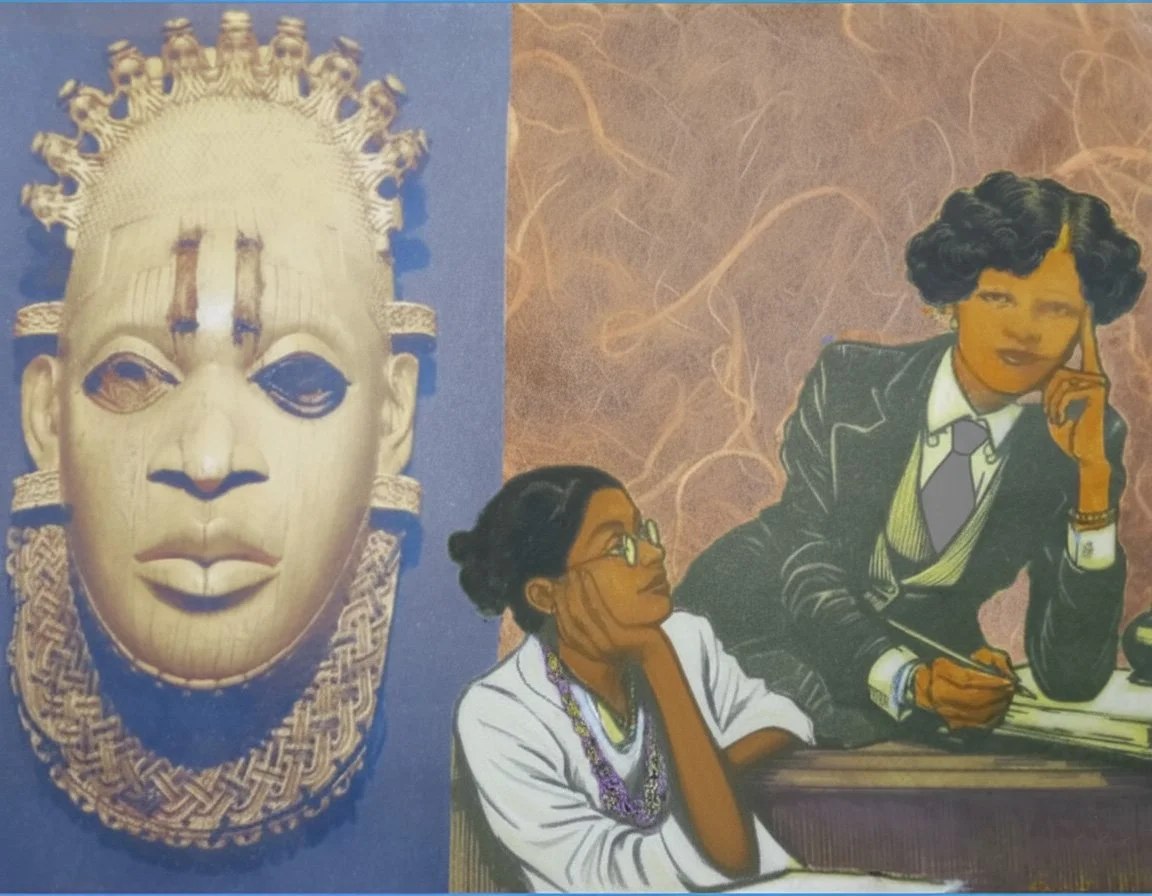

African roots of “cool.” In a Hurston autobiographical story, when the young Zora was dreaming about a future self, she envisioned students like the girl pictured above being enraptured by her older self’s profuse professorial nonchalance. She would be especially erudite as she lectured to her class, leaning over her desk with laid-back attitude — very “cool” (as a coming generation would say). Art historian Robert Farris Thompson explored the African roots of the "cool” concept and said that it has deep connections to aesthetic and philosophical ideas found in West African cultures, particularly the Yoruba of Nigeria.

The Yoruba word “itutu” refers to a quality of inner peace and the ability to maintain composure in the face of challenges as well as a sense of style, charisma and effortless charm.

Ecollective graphic right is paired with mask identified with Idia, mother of Oba Esigie; Benin Kingdom, Nigeria, 16th century; ivory, iron and copper wire; British Museum collection. Photo of mask: public domain via Wikimedia Commons.)

The Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor was designated by the Gullah/Geechee Cultural Heritage Act, passed by Congress Oct. 12, 2006.

Map: North Carolina Gullah Geechee Greenway/Blueway Heritage Trail Project and Carolina Public Press

James Melvin’s New Mercies oil on canvas (above) is similar to the view of Sullivan’s Island in the Lee Keadle photo above the painting. Africans were held on Sullivan’s Island before being sold into slavery. So we feel our tender “new mercies” assuaging the memory of enslaved Africans who entered this country along the southern coastal corridor. James Melvin’s Studio is in Nags Head on the North Carolina Outer Banks at the top corner of the Gullah Geechee corridor.

Photo of painting courtesy of Aspire Gallery, Norfolk VA.

Way down upon the Combahee River

Dramatic appeal of the Gullah Geechee Corridor swamp

Lithograph of Harriet Tubman’s Raid along South Carolina’s Combahee River, illustration in Harper's Weekly, volume VII, no. 340 (1863 July 4) A July 10, 1863 report in Boston’s Commonwealth newspaper, described the waterscape: “About ten miles north of Port Royal Island, Harriet’s station, was St. Helena Island, and between this island and the mainland of South Carolina was the water known as St. Helena Sound. The Combahee River, a narrow, jagged stream that ran about fifty miles into the interior of the State, began at the Sound and on its banks were rice fields and marshes.” Italics added.

The Gullah Geechee Corridor extends across the swampy coastal area of Georgia where Alice Walker’s The Color Purple novel is set.

The swamp crossing scene on the left is from the 2023 movie adaptation of The Color Purple novel. (Still photo sourced from Oprah Winfrey Films).

The movie’s director Blitz Bazawule says that the swamp setting dramatically highlights Shug Avery’s first appearance at the juke joint in this New York Times “Anatomy of a Scene.”

Gullah fisher with hand-woven net. Photo: Doris Ulmann, early 1930s.

Sun rays penetrating swamp trees and water.

Before she began her “A Carolina Rice Plantation of the (Eighteen) Fifties“ series, Alice Ravenel Huger Smith was drawn to swampy terrains that evoked the impressionistic aspect of her figurative style.

Alice Ravenel Huger Smith, Bayou Scene, 1920. Public Domain

During her investigations of the history of the southern U.S. coastal plain, Kendra Hamilton discovered information about what black people called the “feenda” and what their African ancestors called the mfinda.

In Romancing the Gullah, she discusses “feenda” within the context of the subtropical woods and marshes which black people were able to skillfully navigate because of their familiarity with similar West African environs. Back home, the mfinda represented the forest where people would go to experience a deep connection with the spiritual realm.

Kendra Hamilton is a native of Charleston, S.C., with family roots in a “centennial farm” continuously owned-and-operated in a little place in the state called “Ninety-Six” ever since its purchase by black people during Reconstruction.

Hamilton was educated at Duke University, Louisiana State University, and the University of Virginia where she earned a PhD in English with specialties in American studies, especially Southern and African American studies.

That Hamilton would be a poet, politician, gardener and community activist, in addition to being an essayist and scholar was preordained by her Gullah Geechee heritage. Gullah Geechee people are quick to notice when signifyin’ turns into hubris and default to grace.

In Charlottesville, Virginia, where she lived and taught for many years, Hamilton was the first black woman elected to City Council. She also founded the Episcopal Church’s Bread and Roses initiative, which supported two community garden ministries as well as a commercial canning kitchen as a community resource and business incubator.

Kendra Hamilton’s conjoined selves — Gullah geechee gurl and prodigious scholar — are not a contradiction in terms.

Hamilton has a long record of doing work at the intersection of environmental ecologies and culture. Bookended by “Water/Table” in 2004, an installation of Carolina Gold rice plants that created a temporary wetland in the center of the city, and concluding with the design for “Alicia’s Garden” on that site, Hamilton worked with the Spoleto Festival USA’s Places and a Future Artists’ Collaborative on a series of projects highlighting Charleston’s environmental history and the role of embattled Gullah Geechee communities within it.

Kendra Hamilton is certified as a master gardener, trained in bio intensive farming practices , and has taught ecofeminist approaches to community building and ecological conservation in college-level, service learning courses. See this article, for Hamilton’s account of her current life and outlook on a “five-acre farmette” near Clinton SC.

Water is ongoing cyclical change: water, gas, ice … water, gas, ice… .Likewise in Gullah Geechee thought water be the changing same everyting wa' gwine 'round, come 'round.

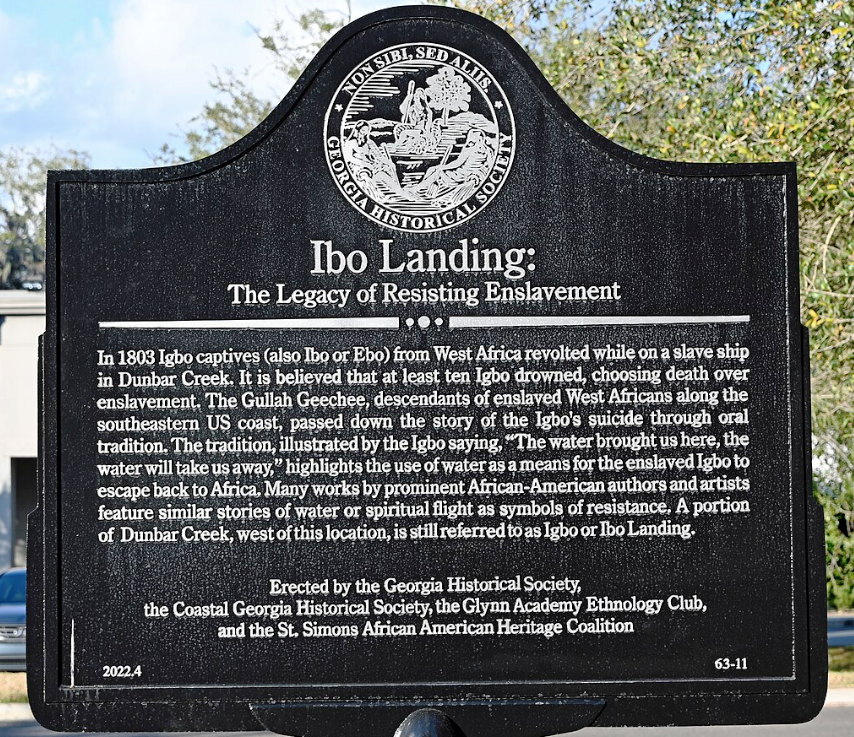

The Gullah Geechee “de wata bring, de wata tek” saying has dual origins: A declaration of resistance: “The water brought us here, the water will take us away,” as noted in the historical marker photo on the right. And the cyclical nature of traditional Gullah thought.

The legend of the Ibo insurrection and mass suicide in the water off the coast called “Ibo Landing" took wings as it morphed into a liberating belief in the unshackled minds of enslaved bodies – that some black people flew home to Africa. The declaration of resistance continued to develop into urban legends, literature and music without the explicit reference to Africa:

At 3:00 p.m. on Wednesday of February, 1931, I will take off from Mercy and fly away on my own wings. Please forgive me. I loved you all.

Suicide note written by insurance agent in Toni Morrison’s novel, The Song of Solomon.

Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina, was the largest slave port in North America. Between 160,000 and 200,000 enslaved Africans passed through it.

Photo of the Sullian’s Island beach by Lee Keadle, https://commons.wikimedia.org gh this port on the way to the mainland and sea islands.

Pastoral landscape and sensibility in Romancing the Gullah

After noting that Jean Toomer’s pastoral sensibility shapes his Cane collection of sketches published in 1923, Kendra Hamilton demonstrates her own pastoral poetics in pointing out the economics and exploitation of sugar cane production that incorporates a creative paraphrasing of Toomer’s atmospheric allusions.

Of the cane that is sugar and the title of Toomer’s novella, she says that the cash crop “... evokes a tragic landscape: layering images of the sugar lands of South Carolina or Georgia or Louisiana – whether plants undulate tall and green over vast acres in the height of summer or lay chopped, supine and burning after harvest, columns of smoke mounting to a blood-soaked sky in late fall … .”

Hamilton also interprets the “pastoral” concept in unexpected ways. In referring to the novel, Porgy, which like the stage play, “Porgy and Bess,” is set in a teeming Charleston tenement, she says that in the southern pastorals of the Charleston Renaissance, it “is time – the sense of a glorious past contrasted with a fallen present – that serves as the productive site of creative tension.” The sense of a glorious pastoral past was one of plantation life where the livin’ was easy, fish were jumping and the cotton and rice reeds were high (if you weren’t the servant singing that lullaby).

The “fallen present” came with the demise of rice production in South Carolina because rice plantations couldn’t survive without enslaved labor.

Bridging Worlds: Kendra Hamilton's Embodied Scholarship

Kendra Hamilton Photo: Presbyterian College

River imagery in Negro spirituals

During a conversation with Kendra Hamilton, the Ecollective editors learned that Gullah Geechee land-and-waterscapes were the inspiration for water-themed spirituals such as “Down by the Riverside,” “Michael Rowed the Boat Ashore,” “Deep River” and “Roll Jordan Roll.

Aquatic cycles

Ibo Landing historical marker. Photo: Jud McCranie. Wikimedia Creative Commons

The Charleston “landscape of correction” included multiple components and most centrally, the old city jail. Photo: Evan G. on Yelp

Du Bose Heyward’s Porgy novel was published in 1925. The staged musical, Porgy and Bess, was based on the novel.

Julia Peterkin, Black April, 1927, set on a fictional South Carolina Sea Island.

African ethnolinquistic groups

Full chart can be viewed here.

In the “Florida Roots and Routes” section of the Romancing the Gullah book, we learn that the “deepest flows in the human tides of the Gullah Geechee Coast were also in some ways the most deeply hidden.”

Hamilton is referring to an under recognized aspect of the Seminole Wars between 1821 and 1858: they were wars over slavery because black maroons had been welcomed into the Seminole nation and the nation refused to refused to surrender them.

Hamilton also charts the flows of the Gullah Geeche human tides to the Bahamas and westward through the southern United States.

African creolization

From a birthright bred at her Gullah Geechee grandmother’s knee and extensive study, Hamilton’s assumes the authority to develop her own anthropological and geological nomenclature and embellish existing names for purposes of place-making

For example, the coastal plain and barrier islands stretching from the Carolinas, through Georgia, to northeastern Florida, and conventionally referred to as the “Lowcountry” and the “Sea Islands” become the “Gullah Geechee coast” in the vocabulary of Hamilton and her colleagues. Designated by an act of Congress in 2006 as a “cultural heritage corridor” managed by the National Parks Service, Hamilton elevates the corridor to a seminal region of cultural geography.

Similarly, “African creolization” and “Afro Creole” are the more specific terms she uses for processes of “syncretism.”

Such alternative nomenclature is not just compensation for the deprivations of racial oppression, it has veritable explanatory power. When rice historian Richard Porcher says, “Without rice, the city of Charleston as we know it today would not exist,” he affirms the authority of Hamilton’s exacting historiography and anthropology.

In the chapter on Zora Neale Hurston, the renegade queen of southernmost Geechee culture, the reader can imagine Hamilton delighting in Hurston’s signifyin’ power when Hurston recalls her younger self imagining her older self as an English professor: “Children just getting born were going to hear about Addison, Poe, De Quincey, Steele, Coleridge, Keats and Shelley from me, leaning nonchalantly over my desk (italics added),” with Poe being the errant yet British-influenced American in the syllabus.

Nonchalant, cool, subtly sassy hauteur is Hurston’s response to having to insinuate herself within white readers’ lowered expectations of black people in general and southern black women in particular. Hurston slyly highlighted “her audience’s ignorance while situating her tale within an alternative Afro-creole geography of conjure, a heterotopia” with “subversive possibilities,” says Hamilton.

Readers should feel free to jump around the Romancing the Gullah book to get an overview of Hamilton’s masterful orchestration of her ideas, materials and tools. And if so inclined, the casual reader could go straight to the Porgy and Bess section where Hamilton reveals that her grandmother knew the real Porgy, Samuel Smalls. An amputee or paralytic gambler and pimp, who sang robustly while zipping around town in his goat cart and always circling back to the Bull Pen, a den of iniquity on Long Alley, Sam Smalls was a much more colorful, larger-than-life character than his fictional counterpart.

Boundaries, fissures, flows

Gullah Geechee phenomena are part of an intertwined whole emanating from what Hamilton calls the “third space” between European and “Othered” (i.e., the African and Amerindian “Other”) origins. And to investigate this space, she is mapping a topological “third space” onto the region’s land and waterscapes. Gullah refers to sea island folks; Geechee to mainland dwellers. The fissures occur in the divisions and confluences of race that construct and eviscerate all notions of purity in the myths of Southern identity.

In the “Landscape and Lineage” chapter of her book, Hamilton quotes from Keith Cartwright’s Sacred Grooves, Limbo Gateways: Travels in Deep Southern Time book.

The boat scene in Julie Dash’s film, “Daughters of the Dust,” is a poignant moment representing human-marine ecologies. As the Peazant family prepares to leave their island home for the mainland, the scene captures the tension between tradition and change, Gullah and Geechee and beyond, and the shift from a life deeply intertwined with nature to one that is more industrial and disconnected from these natural rhythms.

In considering the flowing “languaging of landscape,” Hamilton says “that geechee talk developed in a physical third space, an island-to-inland environment that was literally littoral (i.e., the part of a river, lake, or ocean close to the land). This is a deceptive geography both between the shores of bodies of water … and yet also within the marshes and dense swamps, locales that are neither solid nor earth nor water but a shifting landscape of both.”

South Carolina’s “backwater” country spanned peninsulas and junctions of rivers such as the Congaree and Wateree. And rising above all of the inland waterways in Gullah Geechee memory is the Combahee, the river where Harriet Tubman led the gunboat raid that liberated almost 800 enslaved people on June 2, 1863.

In considering the flowing “languaging of landscape,” Hamilton says “that geechee talk developed in a physical third space, an island-to-inland environment that was literally littoral (i.e., the part of a river, lake, or ocean close to the land). This is a deceptive geography both between the shores of bodies of water … and yet also within the marshes and dense swamps, locales that are neither solid nor earth nor water but a shifting landscape of both.”

South Carolina’s “backwater” country spanned peninsulas and junctions of rivers such as the Congaree and Wateree. And rising above all of the inland waterways in Gullah Geechee memory is the Combahee, the river where Harriet Tubman led the gunboat raid that liberated almost 800 enslaved people on June 2, 1863.

Waterways, not roads, were primal in the evolution of the coastal plain, explains Hamilton, in fueling the brutal domination of land and people in what she calls “the nation state of rice.” It was here “on the prison farms known euphemistically as ‘plantations’ that Carolina gold rice was cultivated by growers who had developed their expertise back home in the Senegambia of West Africa. She calls the lowlands a “nation state” because of the staggering scale of colonial and antebellum prosperity in the capitals that rice built.”

The fabled, doomed “nation of rice” with its grand plantations, was watered by enslaved black people who built the canals and mended the water breaks in the fields. Hamilton traces the rice nation’s almost invisible traces in the contemporary rural landscape and its golden reification in the “imperialist nostalgia”of the Charleston Renaissance of writers and artists who paralleled the Negro Renaissance centered in Harlem and DC during the same interwar period.

Veritable crade of African creole civilization

Environmental anthropology is most prominent in the chapter titled “Toward a Triangular Topos: Landscape and Lineage on the Gullah Geechee Coast,” though it weaves its way through other parts of the book and includes the port of Charleston and the waters surrounding Sullivan’s Island where the enslaved Africans disembarked from the Atlantic passage.

Because, among ports of entry in the United States, Sullivan’s island and the port of Charleston processed the most Africans, Hamilton says that the region is the veritable cradle of African creole civilization.

“The low country is a gateway of terrestrial riverine and marine flows. Water connected this countryside not just to cities like Charleston and Savannah but also to the Caribbean and a broader global empire of trade. ”

Igbo Landing where Africans chose death over enslavement, Glynn County, Georgia

By Jud McCranie - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/

Next steps for illumining the Gullah Geechee “shadow canon”

Kendra Hamilton's triangular "lineage, language and landscape" topos has dense intertwined layers. This essay has mostly focused on the landscape angle. But Hamilton's analysis conflates all three in the chapters on the Charleston Renaissance.

Part of the “Beautiful, historic Charleston” landscape was celestial, a skyline of church steeples, and part was carceral: a swatch of land that held the Charleston city jail, poorhouse, workhouse and medical school. In the Porgy novel, Bess was imprisoned after being caught with cocaine from Sportin' Life. Hamilton cites Bess being in what historian Mauire McInnis describes as an old jail building that was "central to the architectural language of slave control" and part of a "landscape of correction."

In contrast to the Charleston built environment is a glimpse of Ktitawah Island where the Crown character lives "quite comfortably in a homely little shack of driftwood and palmetto fronds."

One of Kendra Hamilton’s key points is that white Americans in general, and particularly white southerners, have become a changed people because of their close physical and social exposure to black people. The “first families” of South Carolina and other white people allowed into their social class claimed genetic purity because their feeling of superiority over black and swarthy peoples demanded it. As an interesting example, she shows how middle and upper class white Charlestonians had some strong Gullah Geechee linguistic traits. And by the time Du Bose Heyward came along, he had the advantage of being able to see the poetic and charismatic character of Gullah Geechee culture and bring it to life in the Porgy novel. His work stands out in the Charleston Renaissance because he could express the winning attributes of Gullah culture and not just from a psyche that had been informed by demeaning racial caricatures.

So within the topos, a "language" angle is Du Bose Heyward's own fluency in Gullah Geechee speech stemming from his close association with black people and the lineage aspect includes Heyward's mother who made ‘good money’ as a performer of Gullah folktales and songs.

Julia Peterkin, another Charleston Renaissance novelist and white "rightful heir" of Gullah Geechee culture, declared that she "spoke Gullah before I spoke English." That speech was called “high Gullah.” When she wasn’t writing Gullah dialogue, Peterkin’s nature writing sensibilities were richly rewarded in her romanticized (very lyrical but prosaic) descriptions of the Sea Island environment in passages like this:

The sun went down in a blaze of glory, painting the sky with fiery reds and oranges that slowly softened into hues of rose and lavender. A gentle breeze stirred the marsh grass, whispering secrets only the fiddler crabs and the sleepy birds understood. The pluff mud, rich and dark, exhaled a salty fragrance that mingled with the sweet scent of honeysuckle blooming in the nearby woods. As twilight deepened, the sounds of the day faded, replaced by the chirping of crickets and the distant croaking of frogs, a symphony of the night beginning its ancient song.

Hamilton relates crossracial intimacies of language and lineage to Laconian and Fanonian theories about racism's impact on inner landscapes: how it affects self consciousness of black and white people on various psychological levels. What does it mean to grow up white in the supremacist south with a psyche shaped by black vernacular speech?

And of course, "lineage" also includes the inconvenient truth for white Carolinians of "miscegenation." Hamilton probes the murky waters of the “impure” genetic and cultural lineages of white southerners by wryly noting that black(ish) Jean Toomer became a member of the then (“lily white”) Charleston Poetry society. This southern “smart set” was quietly grappling with intense racial tensions such as the desirability of biracial and black women and the cross-racial rivalries, jealousies and hostilities lyrically expressed by Toomer in the “Blood Burning Moon” story of his Cane novella.

Hamilton folds this literary knowledge into her understanding of the white Carolinians whose genetic make-up was considered contaminated by ‘pure’ blooded Europeans and Americans such as J. Hector St. Jean de Crèvecoeur, a French émigré to New France who became a citizen of New York.

Crèvecoeur described these white people as diseased and debilitated by the miserable, humid, mosquito and pestilence laden swamps and from breeding with black and indigenous peoples. He also disparaged the multiethnicity of Carolina whites – mixtures of English, Scotch, Irish, French, Dutch, Germans, and Swedes.

“From this promiscuous breed,” writes Crèvecoeur, “the race now called Americans have arisen what then is this new man. He is neither a European nor a descendant of the European hence that strange mixture of blood which you will find in no other country.”

Hamilton says that Crèvecoeur and his kind feared becoming consumed by the wild landscape of the South and its savage people that included other white people.

Deep (psychological) rivers, indeed.

For black people, deep rivers were very symbolic: Deep river, my home is over Jordan. Deep river, I want to cross over into campground. (Lyric from Negro spiritual.)

Hamilton presents an abundance of information and ideas that beg further investigation. The final section of this essay shows one of countless ways that readers can apply Hamilton’s topos their own areas of inquiry.

From Sullivan’s Island and the Charleston port to the “Black Beach”

Kendra Hamilton’s conception of Gullah Geechee creolization being the crucible of African American culture (because the preponderance of Africans entered through the Charleston port) prompts the closer consideration of whether “black” identity should be capitalized.

In "The Black Beach: An Interview with Édouard Glissant,” Glissant, the writer and philosopher from Martinique, says, "For me, to be black is to consent not to be a single being." Glissant sees black identity not as a fixed identity, but as a dynamic process of becoming, shaped by diaspora encounters of West Africans with Africans of various ethnicities, other African-descended peoples, and non-black peoples.

“The constant movement of the tides and the interaction of different elements suggest the ongoing process of creolization and the emergence of new forms of identity and culture.”

The title "The Black Beach," the "Beach" functions as a metaphor for several interconnected ideas:

In addition to referring to Martinique’s beach sands colored black from volcanic ash, the beach is a borderland, a transitional zone between land and sea. The site of departure from African and arrival in the Americas. A space of exposure and vulnerability. And despite its history of trauma, the beach is also a site of potentiality. The constant movement of the tides and the interaction of different elements suggest the ongoing process of creolization and the emergence of new forms of identity and culture.

In "consenting not to be a single being" and affirming the multiplicity of African being, Glissant can be viewed as a model for the evolving self-naming of enslaved African Americans from their various African ethnic names through the assumption of the names: “Anglo-African” (the Anglo-African magazine was published in the 1850s), “black,” “colored,” “Negro,” “Afro-American,” “b/Black,” “African American,” and what’s (more precisely) next.

In codifying an African American identity that is rooted in a specific place (i.e., Gullah Gechee), Hamilton is illuminating the detailed lineage of Negroes who have become nondescript “b/Black.” Other variations include Afrilachian, the black people of Appalachia. People who espouse(d) this distinct identity include the late bell hooks and Nikki Giovanni, and this community-minded restauranteur of Asheville NC.

Not only are the Gullah Geeche and Afrilachians a hybrid of African and European origins, the mix is further amalgamated with variegated Amerindian origins; for the Gullah, the idigenous influences are Cusabo, a group of several smaller communities; Edisto, who lived along the Broad River; Escamacu, a large southern group; Stalame of Port Royal Island; and Kussah, north of Port Royal).

As for the complexity of African-descended lineage, Hamilton uses linguistic examples. Gullah Geeche personal and place names are drawn from various African locales such as Ngola, Gola, Kiss, Giggi), and Hamilton cites this detailed breakdown of Africans brought to the slave-holding colonies and early states:

19.7 Senegambia: 6% from today's Guinea bissau and Sierra Leone; 17.3% from the windward coast (Liberia and the Ivory Coast), 13.4% from the Gold Coast (Ghana); 1.5% from the Bight of Benin (Togo, Benin, and western Nigeria); 2.5% from the Bight of Biafra (western Nigeria Cameroon and Gabon); at least 39% from Angola (southern Gabon, Congo, Cabinda, Angola and northwest Namibia); 0.5% originated in present day Mozambique and Madagascar on the Indian Ocean. African American genealogical complexity is further complicated with European strains that are, within themselves, very mixed.

Because multi-generational African Americans range from the most diverse intracontinental African amalgam on their African side to the most mixed poly-racial peoples on their American side, some black scholars advocate the reconceptualization of African American identity to make it more specific and thorough yet flexible.

In this reconceptualization, generic “black” (lower case) identity can be our common name as our identities become more specifically determined. DNA analysis is getting more precise. And interactive, digital humanities projects (supported by AI) can help us restore the missing pages of our African diaspora histories and genealogies. The projects could map trans-Atlantic migrations, aggregate, correlate and codify genetic and genealogical data, and historical and demographic information.

Projects to formulate African American ethnicities, along with the African creole nomenclature (such “Gullah Geechee coastal plain”) that Kendra Hamilton is developing, can generate a more complete history of the African diaspora and could be the first step in a healing and empowering universalization process. Specificity and unity are synergies.

Lower case “black” identity signifies the complexity of our identity which predominantly includes African peoples whose primary identity is designated by ethnicity and nationality (see the African ethnicities chart on right). Lowercase “black,” “white,” and “brown” signify the differentiation between these groups without reifying artificial constructs of race.

A vast, intricate web of possibilities

The examples in this essay are just a tiny fraction of possibilities for illumining and developing the breadth and depth of the field of inquiry that Kendra Hamilton calls the Gullah Geechee “shadow canon.” Another example on the environmental tip is the exploration of correlations between environmental factors and the Gullah Gechee material culture of handmade fish nets, sweetgrass baskets, rice fanners, Africanesque sculptural hairstyles bound with cords woven from plant fibers on the Sea Islands before the modern period), pottery, grave decorations, ironwork designs, and oyster shells used as building material.

Also, indigo production is an integral part of South Carolina’s environmental and economic history. Indigo cultivation and processing in mid-18th century South Carolina relied heavily on enslaved West Africans who brought established indigo dyeing traditions. Their expertise in cultivation, harvesting, and processing the plant was so vital that some were specifically sought out for it. In these ways, indigo became a major cash crop in colonial South Carolina.

Aa result of environmental changes and real estate development, sweetgrass has become increasingly scarce and difficult for basket makers to find, often forcing them to travel long distances to harvest it or purchase it at higher costs. This scarcity threatens the continuation of the sweetgrass basket making tradition.

This has been an environmental and geo-temporal assessment of Romancing the Gullah. The linguistic and lineage dimensions of Hamilton’s triangular topos are just as deeply fathomable as the landscape dimension.

J.H.

“(sugar cane stalks) lay chopped, supine and burning after harvest, columns of smoke mounting to a blood-soaked sky in late fall … .”