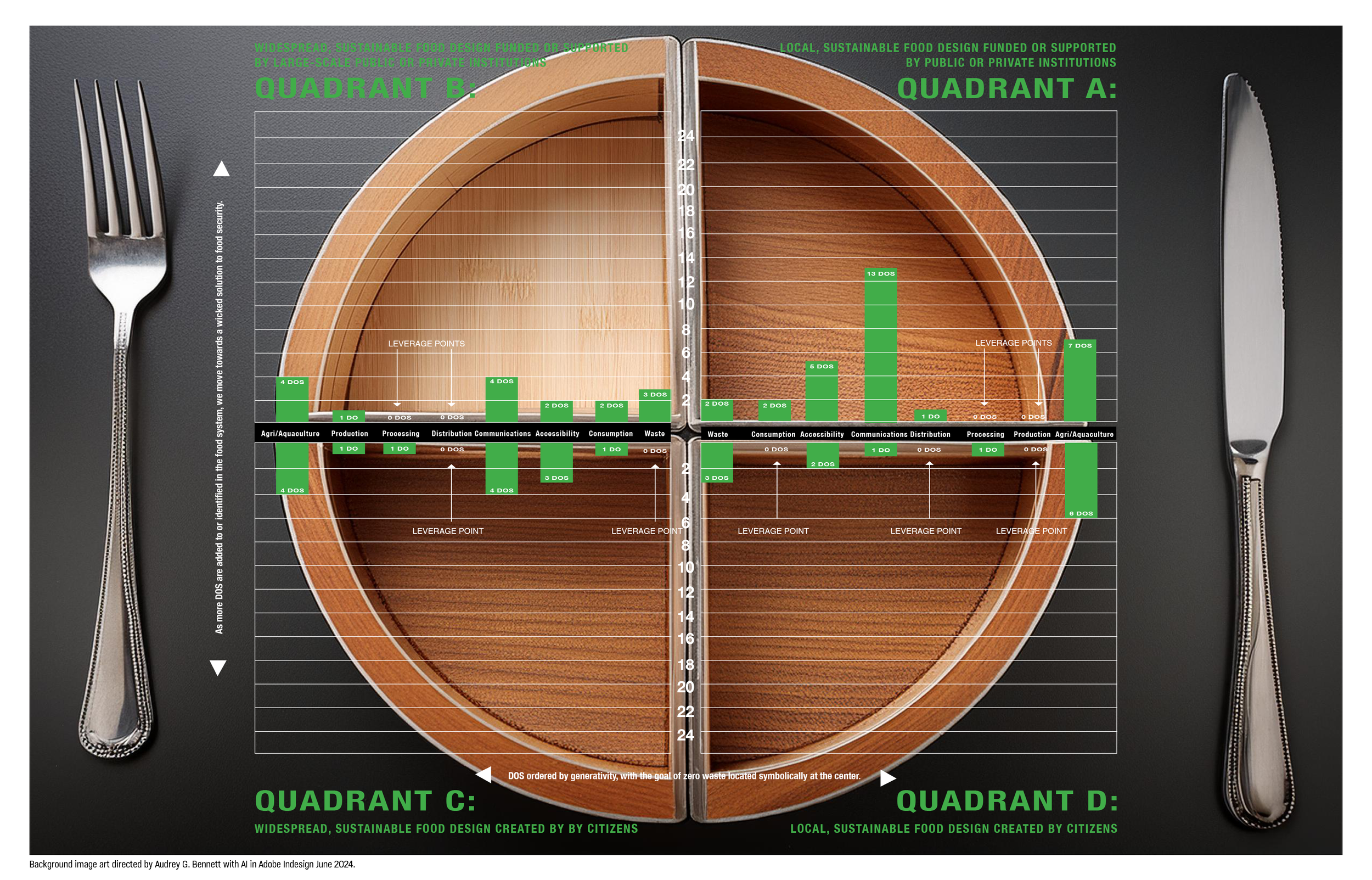

Audrey Bennett designed the infographic above to represent her "wicked" solution to food insecurity. It's a “wicked” problem because understanding its root causes requires grappling with a complex web of social, economic, environmental, and political factors and solutions are often context-dependent and require adaptive approaches. Bennett is translating the infographic into a system that maps design solutions for sustainable food supply and distribution.

Audrey Bennett (UMich Stamps School of Art & Design faculty photo)

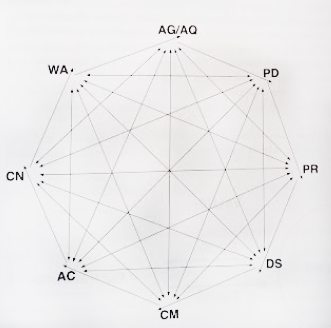

The Critical Mapping book contains a wealth of charts and diagrams, many developed by Audrey Bennett. The above diagram shows eight phases of the interconnected food system: agriculture/aquaculture, production, processing, distribution, communication, accessibility, consumption and waste.

In his foreword to Critical Mapping, Ron Eglash provides this tree photo as an example from nature to show the “wicked” food problem can be addressed by both emergent phenomena (bottoms-up) and top-down solutions. The tree’s sturdy root system keeps it erect so that a human (top-down) solution like constructing a bolster is not needed. But eliminating hunger and malnutrition will require a broad array of approaches at all scales, and across all scales, from bottom to top and back. That’s why critical mapping tools are needed to sort out, analyze, organize, codify and implement the multifaceted problem-solving required to address the entrenched world hunger and local food insecurity problems.

Photo from Michigan Urban Farming Initiative website. Visit here for a full look at the farm.Detroit urban farmer Dazmonique Carr (from Deeply Rooted Produce video)Rescue MI Nature Now project. For more info, visit:

Sensory garden, one of multiple features at Detroit's The Joy Project.

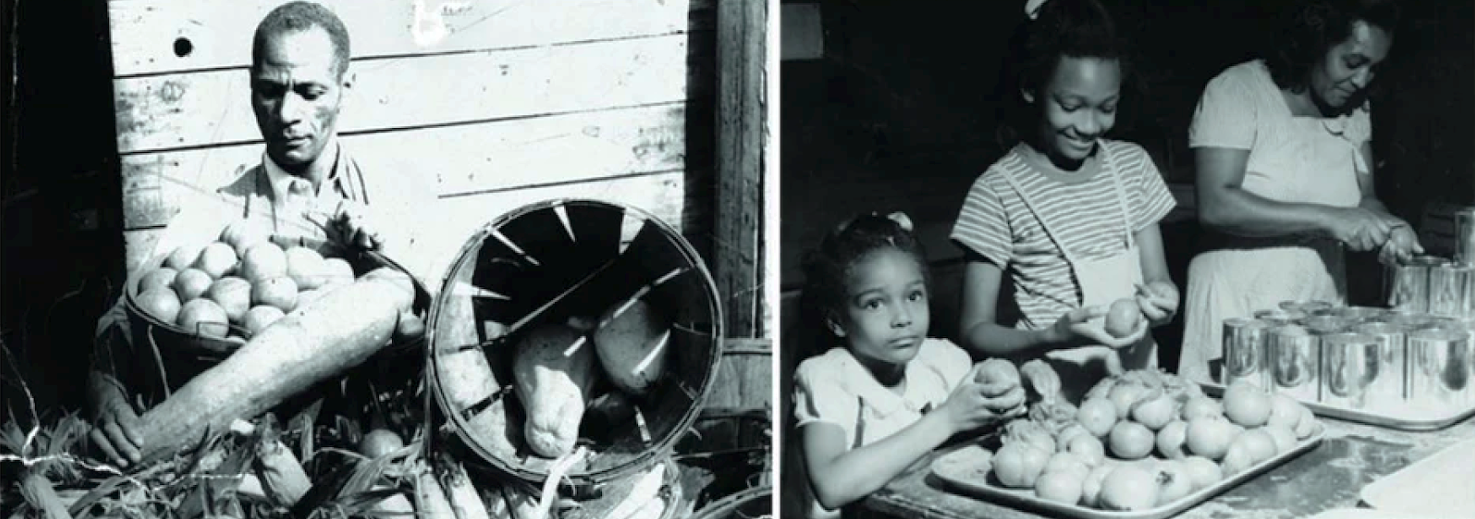

Albert James Moore was an agriculture graduate of Tennessee State University.

In the 1930s in Indianapolis, Moore taught black migrants from the South how to build a self-sufficient community by farming on vacant city lots, starting a grocery store and credit union, and building homes.

Photos: Courtesy of Urban Patch.

Eco-community design solutions to food and health problems

Michele Y. Washington

The earth produces more than enough nourishing food to feed all humanity.

But hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition have been intractable in the USA, other wealthy nations, and developing nations.

Throughout her career, graphic designer and interdisciplinary design scholar Audrey Bennett has pushed the boundaries of her professional disciplines while tackling real-world problems in ingenious ways.

She is committed to using design as a force for multifaceted good and is currently designing wicked solution mapping tools and reimagining a food system that addresses hunger, builds community and protects the health of the environment.

I admired Audrey Bennett’s achievements and then met her in person in 2007 at an AIGA (American Institute of Graphic Artists) Education conference in Nashville, TN. Bennett was teaching at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and thinking forward by conceiving and establishing one of the first virtual international conferences, the Global Interaction in Design Education Symposium (GLIDE). Soon after we met, she invited me to serve on its planning and advisory board.

At the 2010 GLIDE symposium on food, international scholars delivered presentations on food sustainability, food design (design processes applied to products, services, or systems for food and eating), food systems, and related topics.

In 2018, Audrey Bennett was recruited to the University of Michigan in the role of full professor of art and design with tenure. One year later, U-M bestowed upon her an inaugural University Diversity and Social Transformation Professorship for her outstanding work in DEI through teaching, service and scholarship. new position as the director of the M.A. program at Michigan’s Stamps School of Art & Design. She is the first black female graphic design professional to hold a full professor rank in the United States.

As a designer, Bennett systematically focuses on the problem of “food apartheid,” a term describing the significant barriers to accessing healthy and affordable food that often exist in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color.

Unlike the term “food desert,” which merely denotes areas lacking grocery stores, “food apartheid” emphasizes the historical context and systemic discrimination that contribute to unequal food access. City governments have historically disinvested in communities of color. The term, "food sovereignty," means consumers taking more control of their food supply.

Now climate change, extreme weather events and other environmental destabilizations, supply chain disruptions, political conflicts, and wars are increasing global food demands. On the local end of the spectrum various forms of food justice initiatives are being developed. And in between, numerous NGOs, government agencies and business enterprises are involved in food systems. So there’s a heightened urgency for developing ways to visualize and analyze the interconnections and various data points between these and many other factors in order to develop sustainable food systems that can meet the challenges of the present and future.

In Critical Mapping for Sustainable Food Design, (2023), Audrey Bennett and Jennifer A. Vokoun collaborate on tackling urgent food issues with an emphasis on local solutions and community engagement. Vokoun is an associate professor at Walsh University and is director of the university’s Center for Sustainable Food Design. In Critical Mapping, readers can delve into a broad and sundry range of scholarly articles, papers, and case studies, providing a comprehensive look at what is really meant by the term “sustainable.”

"Bennett and Vokoun provide a plethora of sustainable community initiatives including mobile farmers markets, aquaponics, urban farms, community kitchens sack gardens, vertical gardens, farm schools, community gardens, public areas like parks where fruit is free fort he picking, and such -- all economically and environmentally creative solutions.”

Numerous communities of color across the US lack adequate green spaces. These concrete and asphalt enclaves are hotter during the summer and residents have to travel to parks, beaches and trails to cool off and enjoy the majestic, healthy, recreational and spiritual aspects of being in natural environments. Until eco-conscious urban planning and development can adequately rectify this problem, Bennett and Vokoun provide a plethora of sustainable and proven design outcomes that can help poor nutrition in urban areas while increasing access to the natural world. For example, municipal authorities could invite mobile farmers markets to public housing sites and provide shuttles for public housing residents to community gardens.

The co-authors provide numerous examples of successful and sustainable community initiatives including mobile farmers markets, aquaponics, urban farms, community kitchens sack gardens, vertical gardens, farm schools, community gardens, public areas like parks where fruit is free fort he picking, and such — all economically and environmentally creative solutions.

Critical Mapping for Sustainable Food Design charts a bottom-up approach to complex issues often referred to as “wicked problems.” In the book’s foreword, Dr. Ron Eglash, explains the concept of “wicked problems,” as first defined by Rittel and Webber in 1973. These problems, characterized by their complexity and lack of clear solutions, include challenges like climate change, poverty, and healthcare. Ron Eglash and Audrey Bennett, a husband and wife team, have long partnered on projects merging their research areas that overlap cultural geographies, while mapping the differences between the global north and global south.

In the Critical Mapping foreword, Eglash discusses the connection between wicked problems and emergent solutions. He describes how industrial systems like “factory farming” impose order from the top down, destroying biodiversity and replacing it with massive-scale monocropping, pesticides, substantial carbon footprints, soil nutrient depletion and soil erosion.

Flooding the market with refined wheat flour and refined cane sugar leads to a junk food epidemic and ensuing obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular, and other chronic conditions and life-threatening illnesses. Addressing these problems promotes environmental as well as human health. For example, sugar cane production pollutes ecosystems and sugar cane cutters in the Caribbean and in India have been exploited by sugar cane manufacturing companies.

Bennett and Eglash, who live in Ann Arbor, received a grant from the National Science Foundation for the Artisanal Futures project, examining how computing might empower a community-based economy in Detroit. For example, they collaborated with the MBAD African Bead Museum to create the African-Futurist Greenhouse, which uses digital controls to grow indigo, sweetgrass and job’s tears for local crafting. At The Joy Project farm the local founders designed a solar rain harvesting system that worked so well that Artisanal Futures replicated it at five other farms in Detroit. Working with another farm, Rescue Nature Now, they helped fund a digital chicken farming system. The students involved in those projects have now launched their own careers in this area. Kessa Johnson, who worked on the African Futurist Greenhouse, now works as a food systems strategy design specialist at U-M. Kwame Robinson had designed a worker-owned e-delivery system for Artisanal Futures. He is now an assistant professor at Wayne State in Detroit, and is working with Dazmonique Carr’s Deeply Rooted Produce to extend these technologies (including fresh produce vending machines!) to Carr’s zero-waste mobile grocery store. Carr provides fresh produce locally to communities that lack access to wholesome food and composts on a large scale, turning food waste into organic soil.

Growing food in urban settings has led some Detroit farmers to adapt indigenous practices. These growers are well versed in agroecology such as crop diversification, soil management, and mulching. They prefer biologically friendly pest control over toxic chemicals that live on the soil after contaminating the food. Also, gathering rainwater perfectly suits urban growers who lack access to extensive outdoor watering systems.

Communities of color have a long history of taking control of their own nutritional needs. In the 1970s, the Black Panther Party headquarters in Oakland led a national grassroots movement to establish free breakfast programs for children and offered free food to local communities.

An outstanding, multifaceted environmental nonprofit is Urban Patch in Indianapolis. Albert James Moore was agriculture director at Flanner House, founded in the 1930s as a social services agency. Moore taught black migrants from the Jim Crow South how to build a self-sufficient community by farming on vacant city lots, starting a grocery store and credit union, and building homes. In 2011, Albert James Moore’s descendants established Urban Patch in Indianapolis and New York City. They develop and support farming, community gardening, housing, and rain-gathering projects.

Supremacy takes many forms including food domination

At present, the food available to consumers in this country is largely dictated by dominant corporations that shape our supermarket selections. These giants, notably Kroger and Walmart, essentially determine our dietary options.

To put this domination in another perspective, in Critical Mapping, Bennett and Volkoun say that the processed food items in the U.S. diet come from an average of 1,300 miles away and fresh produce from an average of 1,500 miles away!

Nationwide, families grapple with securing sufficient daily sustenance, a struggle highlighted by a recent USDA Economic Research Service Report. We’ve seen a 2.6% surge in food costs from January 2023 to January 2024, followed by a 2.3% increase from February 2023 to February 2024.

A confluence of factors contributes to this inflation: droughts, soaring production expenses, workforce deficits, and logistical upheavals. The pandemic’s lingering shadow, and the Russian-Ukrainian conflict’s impact on the global wheat supply (Ukraine was “the breadbasket of the world”), exacerbates the situation. Moreover, climate change’s onslaught—extreme weather, droughts, heatwaves, and crop diseases—further diminishes agricultural output.

But people can retake control of their food systems by projecting old traditions into the future. Envision communities raising chickens, crafting cheese, catching fish, and maintaining kitchen gardens. There are people still alive today who remember the “Victory gardens”of World War 11.

Alternative growers include hydroponic and aquaponic systems. Their use in this country spans only a few decades but they date back to the Aztec and Mayan civilizations. Both are efficient, soilless farming methods. Hydroponics uses nutrients mixed with water, while aquaponics uses fish waste as nutrients.

Beyond our borders, the Brazilian mandala system cited in the Critical Mapping book stands out as a model — the family farming system used by NGOs in Paraiba, Brazil, to teach low-income families how their fields are used to cultivate nourishing food and provide an income. The mandala tool assesses family farming within the context of four dimensions: economic, social, environmental, and institutional, and is a comprehensive way of monitoring sustainable development for the people and the locale.

To broaden our horizons, designers and community groups can seek inspiration from diverse cultural practices, such as the agroecological methods of indigenous peoples.

Thinking ahead as a designer, design critic, and researcher, I'm advocating for designers immersing themselves in transdisciplinary food design practices with artists, architects, anthropologists, economists, healthcare specialists, nonprofits, public policymakers, scientists, urban strategists, and community collectives rooted in lived experiences. For example, see the Jordan Weber/Walker Art Center project noted below.

Jordan Weber's Community Garden Opening-Day Celebration, Minneapolis, 2021. Credit: Photo Teddy Grimes for Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.s Community Garden Opening-Day Celebration, Minneapolis, 2021.

Michele Y. Washington is a graphic designer and design researcher and writer based in Chicago IL.

Garden hoop spirit rain catcher for urban farm by artist working with community youth

Jordan Weber collaborated with teens on a community garden laid out like a basketball court with two sculptural rain catchers resembling hoops. The hoops collect rainwater for an urban farm which manages the garden. Jordan Weber created this project during a two years residency with the Walker Art Center. Here's more information about the project.