Are humans

the dumbest smart animal?

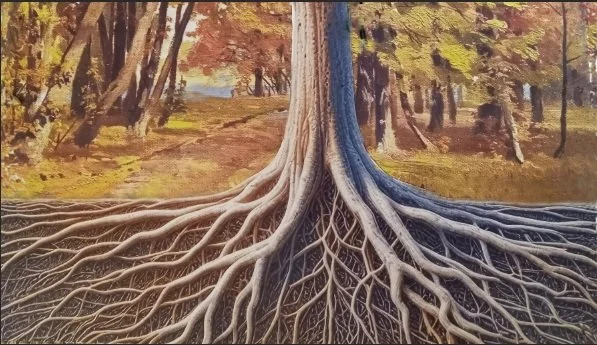

(above)

a depiction of the sense of the separate self (ego), barren and alone

We're the most destructive animal

and the most self-sabotaging

Are humans nature’s dumbest smart animal?

Julian Conway Wilson, Jr.

I’ve become increasingly aware of the intrinsic value of all life. This broad view holds that in addition to respecting all people, animals, plants and environmental systems should be regarded with respect.I’ve given a lot of thought to the afflictions of low-income communities and have realized that all of the afflictions stem from the consequences of what I call “humancentricity” and “human supremacy.” As a social scientist working outside of academia, I went from being a senior federal welfare policy analyst in what was called “welfare reform” to work in the private sector, before returning to focus on the low-income, urban environment as an economic development coordinator. The humancentricity realization began to congeal a few years ago when I was resting on a bench during a walk in Rock Creek Park in Washington, DC. I was looking at the trees when I overheard a guide lecturing about the slavery that occurred in this area and thought about the trees bearing “witness” to this history. Then I read Peter Wohlleben’s best selling book, Hidden Lives of Trees and learned about trees’ powerful survival mechanisms and systems for caring for one another, including communications networks. The tendency to view ourselves as superior to other species and other forms of hierarchical thinking in humans has limited modern human appreciation of the remarkable abilities and unexpected, non-exploitative ways of co-existing with animals and plants that can lead to many beneficial advances for all. This led me to wonder about animals who do not act so self-destructively among their own species while also destroying others. Many contemporary homo sapiens have an ingrained form of superiority driven by the dominant (but no longer needed) "survival-of-the-fittest mentality." ecollectiveIn not appreciating the interdependence of all life, we vertically classify forms of life and prioritize our individual selves over other people and other species. Humans use our “superior” human powers to devalue and exploit each other and the Earth for greed, comforts and gains while overlooking the short term nature of this behavior and its collateral damage. ecollectiveecollective

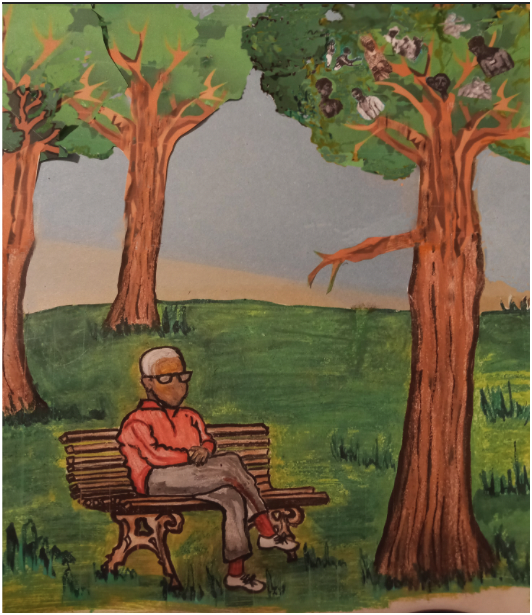

The author sits in Rock Creek Park reflecting on trees. illustration by his granddaughter.

Our ancestors recognized the intelligence, sensitivity and adaptability of animals, plants, rivers, streams and mountains, respecting them as cohabitants and crucial for all-pervasive thriving.

Detail of tree in illustration: ghostly impressions of people enslaved in the area.

The evolution of the species through domination of the fittest is not the only model of evolution. Possibilities for equitable, global human cooperation, for example, are indicated by developmental biologist Michael Levin’s research on how cells cooperate in ingenious ways. If they didn't act so freely, cooperatively and imaginatively, humans would die. In conceptually dividing ourselves from the whole and each other, the human plight remains basically at the caveman level: ‘clubbing others over the head,’ so to speak, with any power that is available to us. The clubs we use include military technology, financial power, leverage of social status, political might, and other supremacist forces. Humancentric supremacists are more likely to tell or give orders before we ask or consult. We prioritize pronouncements over dialogue and collaboration, using words like "cooperation" and "teamwork" as a smokescreen for our self-serving agendas. At the broadest level, the belief in our inherent superiority over all other forms of life and the inanimate world is the cause of the environmental crises. This perspective not only endangers the natural world but leads to racial, ethnic and socioeconomic conflicts that also threaten to reach catastrophic levels.Slavery and predatory capitalism: twin tributaries that flowed into the current crises

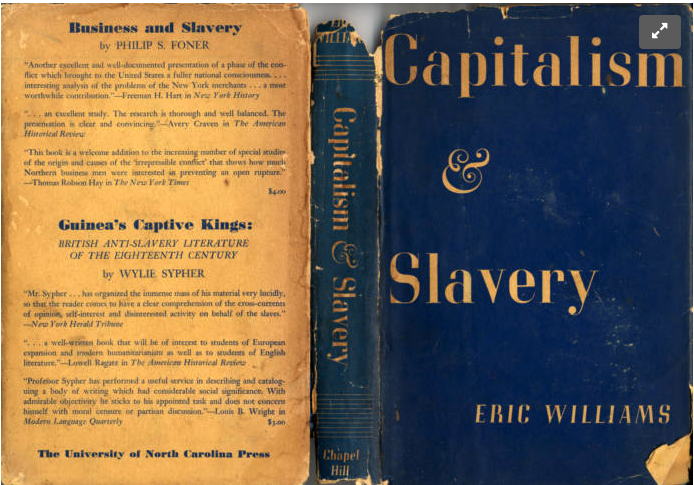

Eric Williams (September 25, 1911 - March 29, 1981) was a Trinidad and Tobago historian and politician who was revered as the “Father of the Nation.”In Capitalism and Slavery, Eric Williams explains how wealth generated from the Atlantic slavery trade and plantation economies was crucial in financing the Industrial Revolution and the rise of capitalism in Great Britain. This thesis can also be applied to the rise of capitalism in the United States.The wealth generated from slavery in the Southern states provided capital that spurred economic growth and industrialization in the North. The transition from slavery to other forms of labor exploitation, such as sharecropping and wage labor, continued to support capitalist development. The products of enslaved labor in the U.S. South and in Caribbean were essential to the growth of big commerce such as textiles, sugar and tobacco and expanded to international markets. he profits from slavery also contributed to the development of infrastructure, such as railroads and ports, which were vital for the expansion of the capitalist economy.Private capital also generated galloping over-production and commodification of natural resources, which led to consumerist (self-indulgent and wasteful) behaviors, which in turn led to the erosion, contamination and destruction of ecosystems, including human life within them. “The Un-restricted hand of the Free Market” drawing and print (The New York Public Library Digital Collections, 1835-05). .

Eric Williams in academic regalia upon earning doctorate at Oxford University in 1938. He went on to teach at Howard University.

(Photo: Eric Williams Memorial Collection Research Library, Archives & Museum, University of the West Indies, Trinidad and Tobago)

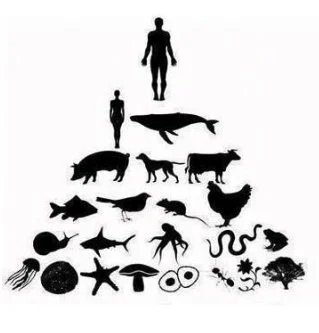

Evolving from divisive “top of the food chain” thinking

and humancentric hierarchy …

… towards multi-directional cooperation

Public domain diagrams: re-envisioned taxonomy from Northern Arizona University online Do-it-Yourself educational labs

Bottom line: we have a hard time seeing win-win scenarios

I’m currently reading Bruce Purnell’s book on love and healing, Caterpillar’s W.E.B. for Transformation. In the title of the book by “Dr. Bruce” as he is known on the street, W.E.B. stands for the “wisdom of the elders and the butterfly.” A symbol of life morphing from death, the butterfly is also a figurative way of expressing how tiny actions like the flapping of an insect’s wings is an inextricable part of the interactive whole of manifestation. “Bruce Purnell went through a lot of hell trying to be who he is.”

A 57-year old giant of a man – tall with long locked hair, Purnell went through a lot of hell trying to be who he is. His own struggles have made him intimately aware of public housing life. Out of that background, Purnell, a community clinical psychologist, has emerged as a liberating, free thinking yet scientific, practitioner. In his book, Purnell points out a primal example of ecosystems being in “reciprocal relationship” with humanity. “Long before humans walked the Earth, the first plants were already agents of transformation. They changed the Earth’s atmosphere’s composition allowing more complex life forms to emerge.” Now they function as our larger lungs because they absorb carbon dioxide and release oxygen through photosynthesis.Purnell considers the butterfly effect concept in weather science and foundational physics. Our small acts, he says, to collaborate among ourselves and with other natural systems can have healing, cascading effects that will ripple throughout the biosphere. Bruce Purnell, psychotherapist and founder of the Love More Movement.

As a public housing specialist, I've pondered long and hard about the social afflictions in low-income communities. Searching for public housing solutions comparable to Bruce Purnell's personal practice fills me with perpetual wonder. Extensive research and writing debate the definitive pathway and I find no definitive conclusion. Even in science, there is dogma. So I began to consider that our human desire for dominance and presumed "intelligence" obscure the best answers.

This painfully manifests in low-income communities. Among those I work with, I see deprivation, despair, bitterness, and apathy. Environmental injustice is an overarching aspect of this; low-income communities lack equal participation in discussions about changing outcomes. Disincentives often outweigh incentives for improving the lives of those suffering. Medical and behavioral health are profoundly tied to environment. And incentives meant to benefit humanity seem to favor the wealthy while further disadvantaging the poor. Many poor people say they have lost trust after so many programs and broken promises. There are proven tools to use to ask people who are affected and help us build inclusive conversations that engage their personal agency collaboratively. But these approaches are not often used or used in a way that gets authentic data that can motivate individual commitment. When planning takes place the people at the top omit core questions about why people have not benefited from the past programs or help them take charge of the outcomes. Finding out how to repair the trust bond and motivate people to become optimistic and strive for improved lives must precede asking people what they want. Also environmental justice emphasis on healthy food, safe spaces, and other determinants of health are too often missing in economic development programs for the poor. When they do exist, they are too often sporadic and not sustained. Health, housing and human and environmental well-being are inextricably connected. Successful alleviation of widespread poverty must prioritize this connection along with (as in the Bruce Purnell model) lovingly serving people who have experienced severe circumstances and who struggle with with trauma and difficult issues daily. From a human services view, the way forward would include new models of public housing emerging in spaces where children can run free in the open air and tumble on the grass. This new model could be an intentional community planned through public-private partnerships based on genuine empathy and understanding of the lived experience of the residents. The community would include life coaching from community-based practitioners and cooperative forms of working and living which would meet the residents' economic, social and cultural needs through a management that would include the residents themselves and economic opportunities within, as well as beyond, the planned community.

Julian Conway Wilson, Jr., is a public housing and community development specialist in Washington, DC.

Crime, substance abuse, family dysfunction and young people’s stunted educational achievement are among the issues that Bruce Purnell addresses in his community-based practice. He understands that, for people who live in desperate circumstances to survive and thrive, personal healing is as critical as external improvements. And he considers himself a fellow "journeyer" with these people in the healing process.